समानुभूति

Samānubhūti

June 24, 2022

Commentary by Ami Bansal and Garima Borwankar

Part VIII

Every year since 2013, in honor of Gurumayi’s birthday month, we receive from Gurumayi a daily virtue throughout June on the Siddha Yoga path website. The virtues for most days of that month remain the same from year to year, so that we may gradually go deeper into our study and practice of them. However, each year on June 24, Gurumayi’s birthday, we receive a new virtue. In this year, 2022, Gurumayi has given the virtue of samānubhūti.

After Gurumayi gives the virtue for June 24, the Content Department in the SYDA Foundation invites a writer or writers to create a commentary on it. Often these writers are Siddha Yoga meditation teachers or scholars who have knowledge of the language in which the virtue is given, and who can explain how to understand the virtue in the context of the Siddha Yoga teachings.

This year, we, Ami and Garima, received the assignment. We felt honored—and excited. We always enjoy working together, and this assignment was no exception.

When we first started discussing and mapping out what we wanted to do, we thought it would be a one-part commentary. Within a couple of weeks we would have said everything we wanted to say, written everything we wanted to write—and the rest of the work would have fallen to you, the reader! However, much to our surprise, we’ve been traveling with you for many months, and what a grace-filled journey it has been!

This is Part VIII of our commentary on samānubhūti, and it is also the culminating chapter.

At the outset of this commentary we had identified, for the sake of this in-depth study, five main aspects of samānubhūti:

- cognizance of equality, nondifference, and oneness with everything (Part I)

- knowledge and perception of wholeness and completeness (Part I)

- the experience of balance and equipoise (Part II)

- awareness of parity that leads to deep empathy, compassion, and understanding (Part III, Part IV, and Part V)

- responding to others with gentleness and nonjudgment (Part VI and Part VII)

From our conversations with many of you, and from the shares you’ve written on the Siddha Yoga path website, we understand you have taken this study quite seriously. You have made concrete efforts to implement what you have gleaned from the commentary and to act on the knowledge of samānubhūti that has been blossoming within you. We feel so proud of you! We mean this sincerely.

It’s been heartening for us to know this, and to reflect on how—because of Gurumayi’s intention and her grace—we all are becoming more aware of the importance of empathy and of helping to bring it forth in all the many parts of this world in which we live. We want to share with you now a fascinating scientific theory that we find analogous to samānubhūti. It emphasizes how thoroughly interconnected we all are and how that connectivity influences outcomes.

Until the twentieth century, scientists believed that everything in this universe is governed by specific laws. These laws would make it possible to determine and predict the behavior of the different systems according to which we’ve categorized this universe (such as our solar system).

In 1961, however, the mathematician and meteorologist Dr. Edward Norton Lorenz discovered that even systems that seemed to operate according to precise mathematics could end up displaying behavior that was very unpredictable. This was the birth of what Dr. Lorenz called “chaos theory.”1

In explaining this theory, he described what he called the “butterfly effect”—how a seemingly infinitesimal change in the initial conditions in one part of the system could lead to huge and unexpected changes in an entirely different part of the system. The classic example he gave was of a butterfly flapping its wings in one part of the world—and how this could lead to a tornado being formed in another part of the world several weeks later.

Now, some of you may be wondering, “Well, this is all very fascinating indeed—but would you please explain a bit more about how this relates to samānubhūti ?”

Yes, we most certainly will!

You may look for and expect to receive samānubhūti from predictable sources, from people you have a direct connection with, such as your family and friends. It is a logical expectation, since those you are closest to are presumably the ones who care about you the most and are invested in your success in life. However, sometimes the most poignant illustrations of samānubhūti can come from the most unexpected of places.

There is a wonderful story that exemplifies this point:

In the 1920s a young man immigrated from Italy to the United States. He settled in the state of Montana and opened a dry-cleaning shop. After twenty years he retired from the dry-cleaning business and took up part-time work as a janitor at a small local college. He continued to work as a janitor for many years.

Upon his death in 2004 at the age of 102, the man bequeathed 2.3 million dollars—which was 95 percent of his wealth—to the school where he had worked as a janitor. It turned out that through frugal living and careful investments, this man had become a millionaire!

The man requested that this money be given away as scholarships to students in need. He explained in his will that because his family had been poor, he’d had to start working at an early age instead of attending school. Therefore, he wanted youngsters of subsequent generations to have what he couldn’t—a good education for a bright future.2

This generous man manifested his samānubhūti in such a way that so many students—people he would never know and who would never know him—were able to benefit.

As this story shows us, samānubhūti can come from quarters where we never even thought to look, and much like the butterfly effect, it is an indication that we are all connected. What’s more, we—each of us—can help to fortify this connection. A person doesn’t have to belong to our community, religion, sect, or culture for us to extend samānubhūti toward them. The virtue of samānubhūti is not about give-and-take. It’s not about extending the virtue in anticipation of what someone might do for us or in response to what they might have already done for us. It’s about giving. When the light of samānubhūti shines in our hearts, we take action. We manifest the goodness in our hearts.

In the Hindi language there is a phrase, khayālī pulāo pakānā, which means “to cook pulāo in your imagination.” You can fantasize all you want about cooking pulāo, a delicious savory rice dish—you can imagine all the spices you’ll add, and the fragrance and warmth of the rice—but if you only cook it in your imagination, how will it satiate your hunger?

Similarly, just thinking “I am a deeply empathetic person,” “I am a profoundly good-hearted person,” “I always wish the best for all,” “There is not a mean bone in my body!” will not support you in making the virtue of samānubhūti manifest. If you do not transmute your intentions into your actions, then that is akin to khayālī pulāo pakānā.

Both our actions and our inaction have an impact on our world and those who inhabit it. The little things become big things. The small moments snowball. If we have the chance to express empathy and we don’t take it—or we miss it—then we are wasting our time. The moments in which we choose not to express empathy accumulate, with each such instance further disconnecting us from our essence, from our true intentions and motives.

The other day, when we were working on this commentary with one of the staff members in Shree Muktananda Ashram, she shared with us how Gurumayi had explained the workings of samānubhūti by giving an analogy based on the ballast under railway tracks. So at this point, we’d like to share with you how we have understood the analogy Gurumayi gave.

The people who first invented railway tracks must have had incredible foresight and knowledge about how to create a foundation that would be strong enough to withstand the weight of a locomotive. What we discovered from our research is that under the railway tracks are rocks—lots and lots of them, filling the base beneath the track. These rocks are of all different shapes and have jagged surfaces. They constitute what is called “ballast.”

What is the purpose of this ballast and why are the rocks jagged? Well, the rocks are jagged so that they can interlock, or fit tightly against each other. By interlocking, the rocks stay firmly in place. This strong ballast evenly distributes the heavy load of passing trains and keeps the tracks from shifting, sliding, or buckling. This then facilitates the steady and balanced movement of the train along the metal tracks.

Another vital role that the ballast plays is as a shock absorber. The ballast helps to absorb the shock of the train’s movement, as well as the noise of metal wheels rubbing on the tracks. It is because of this ballast that we can enjoy a relatively smooth, comfortable, and safe train ride. What a remarkable gift to humanity these inventors have given!

Now let us take a look at how this relates to the virtue of samānubhūti. Everything and everyone on this planet is different—humans and animals, rivers and trees. Living beings come in all different shapes, constitutions, and varieties. We humans in particular have different ways of thinking and doing things, as well as different lifestyles, social statuses, and ideas about how to move through the world. Yet these differences, when united with an awareness of the one underlying principle connecting us all, actually create strength. They give rise to a network of mutual support, a bulwark of steadiness and balance, that helps sustain life itself. This creates fertile ground for the expression of samānubhūti—and in turn makes it possible for everyone to live a beautiful and purposeful life on this planet.

The Roman emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius Antoninus once said: “Men exist for the sake of one another. Teach them then or bear with them.”3 Human beings exist and survive because of our interconnectedness with each other. We are here, on this planet, to help and support each other, to grow and flourish together. Each one of us must do our part, taking responsibility for what we are capable of giving, for how we can contribute to the betterment of this world.

Now that we have all come to an agreement that the virtue of samānubhūti that Gurumayi has gifted us is invaluable, we can also remember another priceless teaching that Gurumayi has imparted to us—and then apply this wisdom to our implementation of samānubhūti. Gurumayi teaches us that, in any endeavor of life, the strength of your own heart is absolutely vital.

What does this mean, exactly? It means that you make the conscious choice to have the strength of your heart—your mettle, your character, your moral fiber—dictate your actions. You don’t act from a place of reactivity—because, for example, you are unable to tolerate someone else’s pain or joy. You don’t act because you want to be rewarded. At any given moment, you are present with whoever needs you to be there with them, since you have recognized that you want to give something, you want to share something. It’s not your emotion; it’s your decision. When you act only from a place of emotion, you easily feel depleted. However, when you act from your viveka, from a place of wisdom and discernment, from the strength of your heart, then you will be energized. And you will always know how to generate more energy.

In this culminating chapter of the commentary, we cannot not mention the importance of being aware of a few of the pitfalls you may encounter in the course of your efforts to demonstrate samānubhūti.

The first is that people will have different reactions to your expression of samānubhūti. Even when you have the best of intentions, and you are certain that your actions are in line with those intentions, not everyone will receive your empathy gladly. They bring their own understandings (or misunderstandings) to the scenario; they have their own perspectives and biases, their own ways of viewing themselves and others, all of which affect their ability to perceive and receive any virtue being extended to them.

It is, to some degree, natural to become attached to the outcome of your efforts to extend samānubhūti. If you’re expressing empathy to someone, you’re doing it so that they might feel better; so that they might feel supported, heard, and understood; so that they find the power within themselves to stand on their own two feet and know what their way forward is. And it’s not that you shouldn’t envision and work toward a positive outcome when performing your act of samānubhūti. However, it’s important that your commitment to acting with samānubhūti does not hinge on that outcome. You don’t express samānubhūti because of the reaction you’re going to get from others. You express samānubhūti because to do so is your responsibility as a human being.

On a related note, you will want to keep in mind that while you express samānubhūti for the benefit and upliftment of others, you are not doing it to pander to them. This leads us to yet another potential pitfall on the journey of putting samānubhūti into action, which is that being empathetic is not about being “a bleeding heart.” It’s not about falling for any display of emotion that someone puts on, and thereby leaving the door open for them to walk all over you.

This can happen quite surreptitiously; it’s not that people will always have the conscious intent to take advantage of you. Sometimes, for example, a person’s emotional appeals arise out of a craving for love, attention, or validation, and they either don’t know or are unwilling to conceive of any other ways to have these needs met. In the English language there is a saying that pertains here: “Give them an inch and they’ll take a mile.” In fact, there may well be a similar expression of this wisdom in your own language that you may want to refresh your knowledge of—and you may want to explore such expressions in other languages as well!

Returning to the topic at hand, we, Ami and Garima, are reminded of a word in Hindi, shoshan, which means “exploitation.” Manipulating, coercing, or subjugating others into extending samānubhūti on demand is shoshan. This is never the context in which samānubhūti should be given—or, in fact, can be given. Remember, samānubhūti is a gift that promotes a sense of self-reliance in the receiver, rather than dependence or entitlement. It supports mutual well-being and nourishes the souls of both the giver and the receiver. Needless indulgence of someone else’s emotions does not help them in the long run, and it can erode your own goodwill as the person giving samānubhūti. It can make you that much more wary of expressing samānubhūti to people in the future.

Now, in addition to being mindful of what the other person may be bringing to the situation, it is necessary that you also be continually aware of your own stance when attempting to extend samānubhūti. Is their response to your efforts a product of their own “stuff,” as it were, or is there something you contributed to the scenario?

For example, it can be dangerously easy to assume a moral high ground in the name of helping someone else—to conflate the very real possibility that you have knowledge that could be useful for them with the notion that you just know better than them. When you do this, your attempts to help come across as patronizing. Even if your advice is sound, it probably won’t be heard. What the intended recipient of your samānubhūti will register, first and foremost, is that you’re condescending to them, that on some level you’re thinking less of them and their intelligence. They might feel belittled by this, even humiliated. In such cases, your intent to support them by expressing samānubhūti actually has the opposite effect.

As you can see from our discussion of these potential “pitfalls,” expressing samānubhūti requires a particular acumen, a nimbleness in how you go about implementing the virtue. It necessitates that you develop a greater awareness of yourself and your motivations, and that you be cognizant that others have a variety of motivations, too.

Imagine now that you are taking a stroll in a rose garden at twilight. You are wearing a beautiful and delicate shawl. A breeze stirs. It catches the edge of your shawl, and as the shawl brushes against a rosebush, it gets caught on the tiny sharp thorns.

You are aghast to see what has happened. Your first reaction is to quickly pull the shawl off the thorns. Then suddenly you inhale the fragrance of your viveka. Your thinking faculty is activated. You realize that you can’t just yank the shawl off the bush. If you do, the shawl will tear on those insidious little thorns. Instead, you need to assess the situation; you need to inspect how deeply the shawl has gotten hooked and determine how best to disentangle it. You need to invoke whichever virtue is required in that moment.

With focus and presence of mind, with gentleness and intuitive understanding, with care not to fray or tear the shawl or to hurt your fingers, you coax the shawl free of this thorn and then that one. You are fully engaged in the moment; you are singularly absorbed in your activity. Slowly but surely, the shawl is becoming separated from the thorns. Moments before, those same thorns had posed such a prickly challenge; now, however, they no longer seem so daunting. The shawl is in your hands—it is completely intact, undamaged. You experience sweet relief. And then, something shifts in the cool night air. There’s magic afoot, and you feel it, you sense it: the scent of the roses, embracing you.

Even after we completed writing this anecdote, we, Ami and Garima, have continued to think about it; we find it so interesting and concrete. When we discussed the anecdote, we came up with a variety of ways that we might approach the dilemma of disentangling the shawl from its formidable adversaries, the thorns. Therefore, we want to put before you the idea that you too can revisit this anecdote and rewrite it for yourself. Exercise your brain; uncover a multitude of possible avenues by which to achieve the outcome of freeing the beautiful and delicate shawl from the hold of the thorns.

You may rewrite this anecdote however you wish. And you may continue to rewrite it—to rethink your approach, to reconceive of how you will act and what virtues you will draw upon. Remember, there is no one right way to reach the goal. What is important is that you make the effort to reach it—first by envisioning your approach, and then by allowing the virtues to find a haven in you, and you in them.

In the same way, you can identify a scenario from your own life that, in hindsight, you would have liked to have handled differently so as to express samānubhūti. How would you approach the situation now? Keep yourself open to see which virtue or virtues wish to come forth from within and become available to you. For instance, would you—and others—benefit from approaching the situation with calmness? With zeal? With vigilance? Each virtue has its own tattva, its own unique essence and principle.

As you “redo” the scenario, see whether the outcome is the same or not. The beauty of this exercise is that you can apply it to situations in which you’d have wanted a different outcome, as well as to situations in which you were able to express samānubhūti—but perhaps there were other ways you could have done so, and now you’re curious to discover those.

In the eight parts of this commentary, we have presented you with several other tools by which you can learn more about, practice, and/or implement samānubhūti and the virtues it encompasses. Here is a recap of those tools, along with a few key examples for you to revisit:

- Dhāranā:

- Self-inquiry:

- In Part III, we spoke about the vault of virtues and the vault of vices, and we asked you to reflect on the choices you’d make when bumping into either of these vaults.

- In Part IV, we asked you to think about why people—including, possibly, yourself—hesitate to demonstrate compassion, even when they may think of themselves as being compassionate.

- In Part V, we discussed the topic of understanding and presented three not-so-straightforward scenarios that call for your samānubhūti. We asked that you reflect honestly on how you would respond.

- In Part VII, we asked you to observe and ask questions about what happens in your mind in the process of forming a judgment.

- Tools for Connecting Within:

- In Part II, we referred to the Siddha Yoga practices, such as meditation, svādhyāya, and sevā, as important means by which we can experience the state of equipoise.

- In Part V, we spoke about the breath, mantra japa, and affirmations as means to restore inner balance.

- In Part VI, we brought your attention to Gurumayi’s teaching Pause and Connect.

- In Part VII, we explained how Witness consciousness is a way to purify your chitta and practice nonjudgment.

- Scientific Facts and Theories (for your further research and study):

- In Part I, we spoke about the theory of quantum entanglement, to describe the interconnection of everything on this planet.

- In Part III, we spoke about the neural responses of the brain that are associated with our ability to resonate with another’s feelings.

- In Part V, we briefly explained the workings of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, which is useful to understand if we are to understand ourselves.

- In Part VII, we referenced the enormous capacity of the brain to change, learn, and adapt, so that it doesn’t get stuck in making erroneous judgments.

- In Part VIII (this part), we cited chaos theory in our explanation of how empathy can come from all different, and even unexpected, sources.

- In Part VIII (this part), we explained the analogy Gurumayi gave of the ballast under the railway tracks, and how this is akin to the expression and fruits of samānubhūti.

You might think of these ways of learning about and practicing the virtues to be like so many musical instruments. Each has its own unique timbre, and together they create a magnificent symphony in life.

We continue to be impressed with how you have been studying and implementing samānubhūti so conscientiously and effectively. As one of you eloquently shared on the Siddha Yoga path website: “A very interesting and beautiful immersion is subtly taking place in my daily life that seems to be rearranging my thinking.”

Everything we do on the Siddha Yoga path is guided by Gurumayi’s teachings. So, as you continue your study of samānubhūti, we want you to hold in your awareness this teaching from Shrī Gurumayi:

The mind is powerful; be mindful how you manage it. Intentions are strong; create yours with care. Interaction with others is dynamite; hold on to your heedfulness. Cultivating the virtues is paramount; make time to give it a try. Samānubhūti it is.

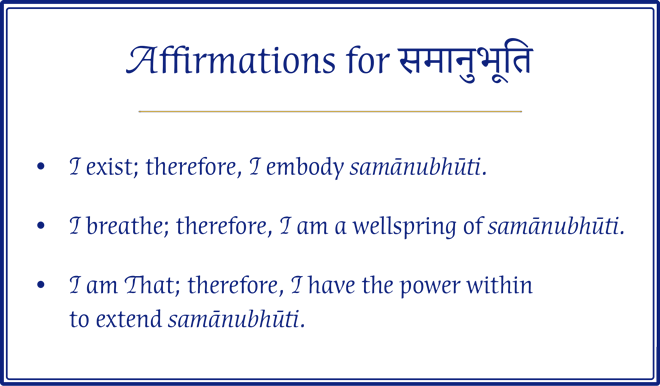

For each of the commentaries on the sadguna vaibhava, the virtues that Gurumayi has given for her birthday month, Gurumayi has given us an affirmation to practice. These affirmations are imbued with Gurumayi’s grace and blessings. They are a means by which we hold the virtue in our awareness, experience its tattva, its essence, in our being, and come to embody it.

For the virtue of June 24, 2022—samānubhūti—we are receiving three affirmations from Gurumayi. These affirmations are for us to study, contemplate, and make a daily practice of repeating to ourselves, silently or aloud. As we practice in this manner, we will find that there is a greater chance for samānubhūti to become real for us—to become second nature to us.

1See, for example, MIT Technology Review, https://www.technologyreview.com/2011/02/22/196987/when-the-butterfly-effect-took-flight/.

2See CBS News, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/janitors-will-is-23m-surprise/.

3Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, and Epictetus, Enchiridion (Chicago: The Henry Regnery Company, 1956), p. 108 (Chapter VIII, Meditation 59).